While the coronavirus pandemic has had a severe impact on the entire planet, the magnitude and extent of the damage has been anything but universal. COVID-19 appears to have placed Black and Hispanic workers in a considerably more precarious situation, in terms of economy and health, compared to their white counterparts.

Given that the current variant of coronavirus is one that has been never encountered by humans before, one of the main reasons for the virus’ uneven racial impact is due to pre-existing social and economic conditions that are still prevalent today and have improved very little since. In terms of both health and economy, widespread racial disparities in status of health, access to healthcare, employment, salaries, housing, revenues, and poverty all contribute towards a greater vulnerability to the virus.

It’s seen that the black and brown communities, along with other minorities, share many experiences with their white counterparts that make them equally vulnerable to the virus. But there are a few important distinctions that need to be made between these groups of people, which must be understood in order to effectively combat the virus’ adverse and disproportionate effects towards the health and economy of the marginalized people.

The pandemic’s impact on black workers

In the COVID-19 economy, there are three main kinds of workers: those who have lost their jobs and are facing economic insecurity, then there are employees who are classified as essential workers and are facing health uncertainty, and lastly there are people who can continue working from the comfort of their homes. Unfortunately, black employees are less likely to fall into the final category. They have experienced unprecedented employment losses in these couple of months (March 2020–May 2020), as well as the economic catastrophe resulting from the same. They are also predominantly found among today’s vital workers, who continue to go to work despite their inability to maintain necessary social distance from their coworkers and clients due to the nature of their jobs, thereby having to put their own health and that of their families’ at risk.

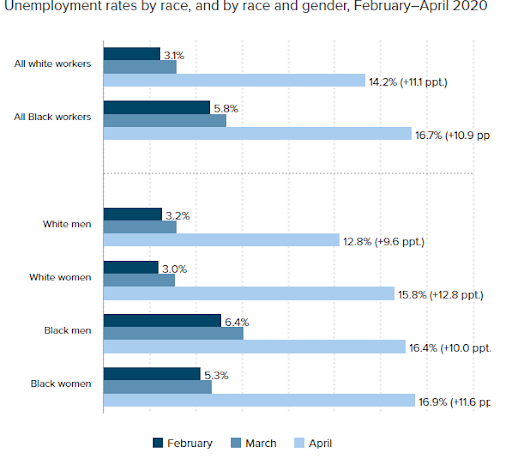

The rates of unemployment in the 3 months (February to April) for the white and black employees are shown in the figure below:

The benchmark for the pre-pandemic economy can be seen in February. It’s noticed that the black unemployment rate has remained persistently much higher than the rate of white unemployment, even in the toughest of job markets. Both began to rise in March before soaring in April. According to the most recent data, the black unemployment rate is at a record high of 16.7%, while the white unemployment rate is at 14.2%.

Financial Risk and Covid

Not only are black employees losing jobs at an alarming rate, but those who have managed to retain their job positions are more likely to work in critical jobs on the front lines of the economy. Many studies point out that black workers make up for a disproportionately large percentage of these critical employees who are required to put themselves and their families at increased peril of contracting and spreading COVID-19 in order to make a sustainable living.

Overall, one out of every nine workers is black, accounting for 11.9% of the workforce. Also Black laborers constitute around one-sixth of all front-line industry workers. While this prevents them from losing their employment in the short term, it also puts them at higher risk of contracting the COVID-19 while working.

Before the pandemic swept through the United States, the black laborers and their families were already in a financial crisis. Because black families have historically encountered higher unemployment rates, lower incomes, and much fewer cash reserves to fall back on, as well as substantially higher rates of poverty than their white counterparts, the pandemic and its related job losses have been particularly detrimental for them. The current economic damage to these people and their families has been exacerbated by their previous vulnerabilities.